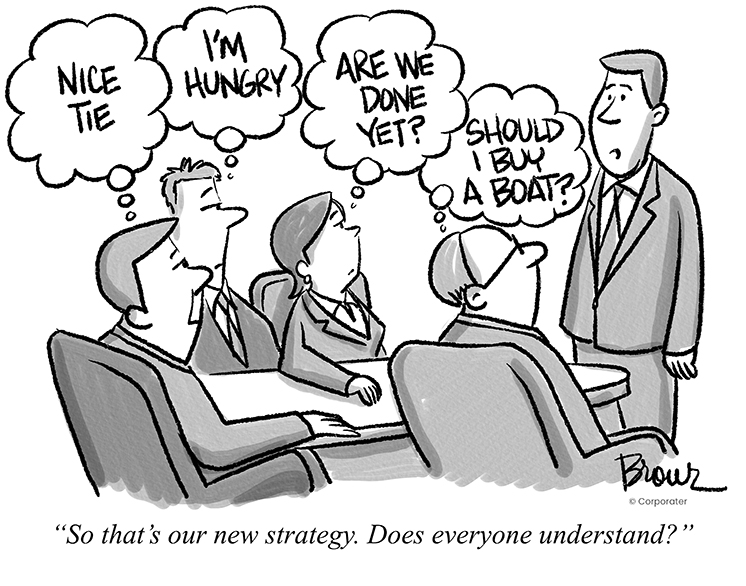

In a separate chapter, we noted the problems that can occur when organizations developing a strategy execution system don’t agree on the terminology they will employ during the process. Confusing the definitions of standard terms can lead to conflicting messages, puzzled employees, and a good deal of skepticism regarding the entire implementation.

While the effects of this nasty tendency have been apparent to us for years, it was only recently that we learned one reason why it may be so common within organizations. At the root of the problem is a phenomenon psychologists term “closeness-communication bias.” i Simply put, the theory suggests that people commonly believe they communicate more effectively with close friends than with strangers. The belief is based on the assumption that a well-known acquaintance is in possession of the same information the speaker has, eliminating any need to provide a longer, more detailed explanation. Their shared history creates a sort of assumed shorthand, removing the necessity to fill in any blanks that may actually stand in the way of true understanding. As one researcher put it, “Our problem in communicating with friends and spouses is that we have an illusion of insight. Getting close to someone appears to create the illusion of understanding more than actual understanding.”

The bias can lead to wildly inflated estimates of the ability to successfully communicate. In one simple example, researchers worked with spouses who believed they shared a solid communication footing and were always “on the same page.” To test this belief, the researchers asked one spouse to utter a common term such as “It’s getting hot in here” to determine if their partner was more adept at interpreting their meaning than a stranger. While the spouse uttering the phrase may have simply been suggesting the air conditioning should be switched on, the other frequently translated it as an amorous advance. As it turns out, accuracy rates for spouses and strangers were statistically identical in the study.

The research we found on this topic was restricted to close friends and spouses, but it seems logical to imagine the same pernicious effects could plague communication within organizations. Coworkers are in close proximity to one another for long periods, have a shared corporate history, and undoubtedly make assumptions about the amount and type of information possessed by their bosses, peers, and subordinates. In this context we can easily imagine a manager charged with communicating a new strategic direction to their team omitting subtle, yet important points based on their faulty assumption that the team is in possession of the same base level of information. When team members begin to make decisions that aren’t consistent or, in the worst-case scenario, downright contrary to their boss’s intentions, confusion and frustration are quick to appear.

To learn more about this phenomenon try:

- Asking your team if they feel you’re all on the same page

Hopefully, you’ve created an environment in which people feel safe in suggesting they may not always fully understand the missives coming from the CEO’s office. - Testing it

If you’re the team leader, write (on a flip chart or computer) your top three priorities for the next six months. Give everyone five minutes to reflect on it, then go around the room, having each person report on how they interpret the priorities. Is everyone saying the same thing? If not, you have a problem. - Challenging your assumptions

Ask yourself what you’re assuming when you share information. How much does your team really know? Could they possibly have knowledge of the subject that you’re currently lacking?

The small investment you make in thinking carefully about how close you really are (from a knowledge standpoint) with your team will pay significant dividends in enhanced understanding and ultimately better results for all.