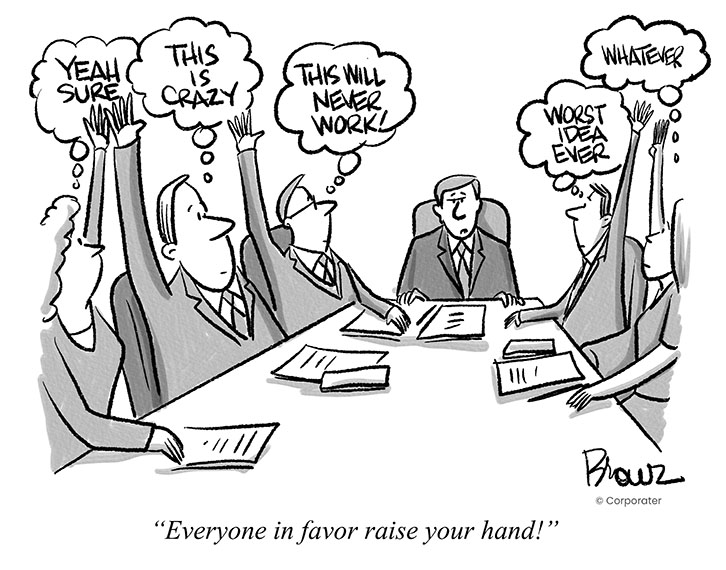

Quick quiz: What do Watergate, the Bay of Pigs disaster, and the escalation of the Vietnam War have in common? Answer: They’re all consequences of the phenomenon known as “groupthink.” The examples cited above are well-known policy blunders, but groupthink is certainly not limited to the halls of government. Chances are you’ve experienced or witnessed it in your own organizational environment. Groupthink is characterized by a cohesive group’s desire for unanimity above all else. When the phenomenon takes hold, members of the group will suppress conflicting opinions, avoid evaluation of alternative courses of action, rationalize in order to discount outside warnings, and ultimately be much more likely to make risky (and sometimes unethical) decisions.

In his seminal book on the topic, Irving L. Janis carefully enumerates the tragic outcomes of the policy decisions noted above, consistently demonstrating the role groupthink played in the deliberations of otherwise astute and intelligent men. For example, he notes that when President John F. Kennedy and his inner circle were making plans for the doomed Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba, the group made six assumptions — each unquestioned and unchallenged — that all later proved to be incorrect. Each member of the team later documented their private misgivings, but noted that the power of cohesion within the group was so strong, dissenting viewpoints were never uttered, and thus serious debate was muted.

As noted above, the prevalence of groupthink is also alive and well in many organizational boardrooms. Despite calls for diversity, many executives tend to surround themselves with like-minded thinkers who are unlikely to deviate from the gravitational pull of the team. This often results in risky or unethical actions that fail to receive the proper scrutiny they deserve before being initiated.

Prior to launching any major initiative or strategic shift, here are some tips to ensure your team is not falling prey to the many harmful effects of groupthink.

- Assign a “devil’s advocate”

Have one member of the group assume the role of contrarian, critically examining the team’s decisions and offering conflicting points of view. This advocate need not be strident or rude, but simply raise new issues by asking basic questions such as “Shouldn’t we give some thought to …?” “Have we considered …?” “Are we overlooking …?” In order for this role to prove effective, however, it is crucial that the team’s leader genuinely support it and allow for dissenting opinions to surface. If it’s a “token” role, results won’t change. - Hold a “second chance” meeting

Group cohesion is so powerful that in the moment it will often suppress even the most vocal critics of a proposed decision. Therefore, to be certain there is true unanimity around a course of action, before the final vote is taken or decision made, the leader should instruct each member of the team to reflect on the discussions in a different environment. Away from the often dissent-stifling confines of a conference room, team members can critically challenge the decisions, call on outside experts, and yes, even sleep on it, before reconvening to come to a final conclusion. - If all else fails, drink some wine

In his book, Janis notes that whenever ancient Persians made a decision following sober deliberations, they would always reconsider it under the influence of wine. This being a cartoon book we expect you to take that advice for what it’s worth and also consider the possible impact of what is colloquially known as “drinking thinking.”

Humans are social creatures, and whether at work or play, we naturally align in groups. Teams, families, clubs; they’re all comforting and supportive structures for our psyches, but in these environments it’s easy to fall under the spell of cohesion and consensus, often resulting in suboptimal decisions resulting from groupthink. Keep your eyes open to the impact of groupthink in your team, and your decisions will be better for it.